By Vivekanand

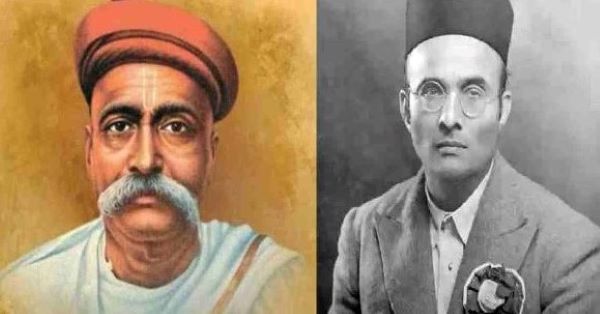

Bhartiya Janata Party’s (BJP) phenomenal victory in the 2014 general elections has brought the idea of Hindutva to the surface in a more pronounced way. The two of the greatest Hindutva ideologues, Lokmanya Tilak and Swantaryaveer Savarkar, can rightfully be attributed as some of the forefathers who laid the foundations of this thought. Therefore, it’s apt to understand the relationship between these two great men who continue to guide Bharat’s destiny in the present as they did in the past.

Tilak must have been one of the very few congressmen who said that Bharat is a Hindu Rashtra. As per the accounts of many scholars writing on Savarkar, he carried forward Talak’s legacy. Prof. Ashok Modak, former professor at Mumbai University observes that with the passing away of Tilak on 1 August 1920, the Politics of Bharat led by the congress took a wrong turn. Savarkar said that Tilak sought Muslim support as a tactical move but Gandhi translated that into a strategic stance something that Nehru translated into a program. Seeking Muslim support has become a single-point programme in the Congress Party after Nehru’s death.

On 28 May 2023, as we observe the 140th birth anniversary of Veer Savarkar, it’s important to deliberate on the ideological legacy that he inherited from Tilak. It’s pertinent because the dummy ideas of secularism have disastrous consequences on our social and political lives. Tilak’s influence on Savarkar can be gauged from the fact that he called Tilak Gurunamguru (the literal translation of the term can be ‘master of the masters’). The scholars and biographers who tried to follow the lives of these two great personalities of modern India have observed that there exist several commonalities between them.

Savarkar, in his autobiography, has quite clearly mentioned Tilak’s influence on him right from his childhood and youth in Bhagur (Savarkar’s native place) and Nashik where he lived till he was 19 years old. Even as Savarkar moved to Pune to study at Fergusson College, he remained in constant touch with Tilak who in turn helped him in many different ways. When Savarkar went to study in London, it was on the recommendation of Tialk that he got the fellowship so that he could take care of his accommodation and studies. Savarkar has also maintained in his autobiography that while leaders like Dadabhai Nouroji, Firozshah Mehta, and Mahadev Govind Ranade were pro-British in their thoughts and deeds, Tilak was purely pro-Bharat. Tilak never took up the British Government’s job. In fact, in one of his writings in Sanskrit, Tilak ridiculed the people who were the recipients of British favors saying… “How could a man who has learned from the British teacher in his childhood, who was in a British job in his youth, and who is receiving British pension post retirement become Bhartiya in his thoughts and deeds?”

It’s not an exaggeration to state that if Swami Vivekanand was a warrior Sanyasi (Yoddha Sanyasi) then Tilak was a warrior family man (Yoddha Gruhasthashrami). When Swami Vivekanand established the glory of the Hindu religion at World Religious Conference held in Chicago in 1893, Tilak in the very same year started public celebrations of Ganeshotsva in the city of Pune. In the year 1897, when Swami Vivekananda came back to Bharat, Tilak was asking the Chafekar brothers if they hated that atrocious Rand so much, then how come he was still alive. Therefore, Savarkar said that Tilak was purely pro-Bharat in his thoughts and actions.

Tilak started public celebrations of Ganeshotsava and celebrations of Shivaji Maharaj’s birth anniversary by the end of the 19th century. His motive was to highlight the contextual relevance of the Hindu religion. In 1905, when Lord Curzon partitioned Bengal, Bharat witnessed its political awakening under the leadership of Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore.

Romain Rolland, the writer of Swami Vivekananda’s biography ‘The Life of Swami Vivekananda’ writes…in 1897, while addressing a public gathering in Madras (today’s Chennai), Swami Vivekanand challenged Bhartiya people to leave everything aside for the forthcoming fifty years and worship only Bharat Mata. Fifty years after Swami Vivekananda’s speech in Chennai, Bharat became freed from British rule. Romain Rolland, further in his biography of Swami Vivekanand writes, people in Bharat started to realize Swami Vivekananda’s predictions soon after his death in 1902 when the entire Bharat rose against Curzon to oppose his plans for Bengal’s partition.

Then sixteen-year-old Savarkar was observing these events with keen interest and learning a great deal from these two idols (Swami Vivekananda and Tilak) of his life. No wonder then in 1898 sitting at the feet of the idol of Goddess Ashthabhuja (Mata Amba Jagdamba), he vowed to toil all his life for the glory of Bharat Mata. Such examples of extreme sacrifice for one’s motherland are rare to be found in the history of India’s struggle for independence.

In 1902, at the age of 20 Savrkar went to Pune for higher education in Fergusson College. While in Pune he challenged British Empire in his poem saying nothing is eternal; the great empires like Greek and Roman have perished so would the British Empire in Bharat. In 1905, he sets a pyre of foreign clothes in the presence of Tilak. In 1906, Savarkar went to London for his studies in law but had no intention to confine himself to the studies alone. Moreover, he wrote to the speaker of the British Parliament to allow him to remain present in the Parliament when Bhartiya issues are tabled for discussion.

Savarkar was merely 24 years old, still studying in England when he wrote ‘India’s First War of Independence: 1857.’ In this book, he delved deep into research and came out with astounding observations stating that the events that took place in 1857 were not sporadic ‘sepoy mutiny’ or merely rebellion against the British East India Company but were the manifestation of Bhartiya people’s aspiration for their own rule by overthrowing the British rule. At the same time, he wrote History of Sikhs.

His revolutionary activities did not remain hidden from the British and he was soon to be arrested. A few days before his arrest, he wrote a poem for his elder Brother Ganesh Savarkar’s wife who he held in the place of his mother. That poem is famous as ‘Majhe Mrutyupatra’ meaning ‘my will before death.’ In that, he writes… “our family has sacrificed everything for the cause of our motherland; our home, my brothers (elder brother Ganesh and younger Narayan), her and his wife, his newborn child so much so that he is even dedicating this poem also to her (his motherland).” In that poem, he also writes it’s due to efforts such as his, the political situation in Bharat was changing over the previous eight years.

The revolutionary activities in Bharat had become so prevalent that from 1902 to 1910, not for a single day could the British rule India with ease. It’s now a known fact that Savarkar in all these years was writing, organizing, and inspiring revolutionaries and even sending pistols and literature for the spread of revolutionary activities in India. It’s only due to his inspiration that Madanlal Dhingra killed Curzon Wyllie at Imperial Institute in London on 1 July 1909. Anant Kanhere also derived inspiration from the revolutionary activities of Savarkar and killed Jackson, collector of Nashik district on 21 December 1909.

During his stay in London, Savarkar regularly contributed columns in the Kesari, a newspaper edited and published by Tilak. In 1908, Tilak was sent to Mandale Jail for six years of strict imprisonment (from 1908-1914) on the charges of sedition. Savarkar, while studying in London, organized a condemnation meeting to that effect. It was attended by prominent Indian National Congress leaders such as Lala Lajpatrai and Bipin Chandra Pal. Gopal Krishna Gokhale too was present at that time in London but unfortunately, he refused to be present at the meeting.

Savarkar had the highest regard for Tilak as a child in Bhagur (Savarkar’s native place in the District of Nashik), Nashik, Pune, London, and even in the Adman Jail. In 1916, Savarkar laid the foundation of ‘Hindu Rashtra’ in the Andaman Jail along with his inmates when Tilak made his famous pronouncement “Swaraj is my birthright and I shall have it”. It’s pertinent to mention that his notions of ‘Hindu Rashtra’ were not exclusive but had an equal place for Muslims, Christians, Jews, Zoroastrians, and other non-Hindu creeds in Bharat.

On the other hand, Tilak too had great affection for Savarkar all his life. The usage of words written to Shymji Krishna Verma recommending Savarkar’s name for admission and fellowship for his studies stands as testimony to Tilak’s feelings for Savarkar. When Tilak was traveling to England, the ship he had boarded had to halt at Eden Port for two days. Tilak’s aid Namjoshi writes in his memoirs that when he went to see him in his compartment, he found Tilak carrying Savarkar’s prosecution papers in his hands. He was all too worried for Savarkar as the charges against him were severe. Various published accounts of the lives of these two great men clearly suggest that they shared affectionate feelings for each other.

Savarkar opposed pseudo-secular tendencies tooth and nail all his life. His historic speech in 1937 as a President of Akhil Bhartiya Hindu Mahasabha has quite clearly spelled out the ideals of Hindurashtra. At this conference held at Karnavati, Savarkar unequivocally pronounced that Bharat is a cultural nation whose soul lies in Hinduness. After 80 years of Savarkar’s speech, the stunning performance shown by BJP in the state assembly elections in Uttar Pradesh under the leadership of Yogi Aditynath in 2017 has proven that Muslims with their Islamic ideals cannot exercise veto power to determine the destiny of this nation. Savarkar or Tilak never intended to treat Muslims as second-grade citizens but wanted them not to exercise their veto power.

In 1906, a Muslim representation under the leadership of Aga Khan went to meet Lord Minto and demanded that Muslims should get representation across governing structures in Bharat from top to bottom. They further demanded that such a representation should be commensurate not only with their numerical strength but their political influence also because they were ruling Bharat before the British came. Such an outrageous tendency on the part of Muslim leaders sowed the seeds of the separate state of Pakistan for Muslims.

Even the moderate leaders like Gopal Krishna Gokhale vehemently opposed such demands. Gokhale, in his speech on 11 July 1909 in Pune, had said there was no truth in the Muslim claim that they ruled India before the advent of the British. He further noted that by the time the British came to India, the Mughal power had greatly weakened and was on the verge of extinction. Moreover, the Marathas and the Sikhs had become all-powerful and exercised substantial influence over the vast territory of Bharat. In fact, the British snatched Bharat’s rule from the Marathas and Sikhs and not from Muslims.

Savarkar firmly held that Bharat, from Himalayan peaks to the Indian Ocean, was a Hindu Rashtra. Furthermore, he firmly believed that the precepts of Hindu Rashtra or the formation of the Hindu Mahasabha were not shaped as a reaction but as a result of the deeply held conviction that Bharat is a culturally Hindu Rashtra. Therefore, he challenged the notions of Muslim supremacy over Hindus. He quite categorically asserted that Muslims were welcome in the process of nation building but Hindus would not keep quiet if they held on to their supremacist view.

Savarkar’s idea of Hindu Rashtra was guided by realism in domestic and foreign policy matters. Swami Vivekananda and Tilak’s pragmatic ideas remained his guiding principles throughout his thoughts and strategies. Both Tialak and Sawarkar were the votaries of strength, a fact that could be found in their speeches and writings. For example, in the book ‘Gitarahashya’ borrowing from the Gita, Tilak has placed a great emphasis on strength. After Swami Vivekananda’s death, Tilak wrote a column in Kesari in which he observed that Swami Vivekananda was a sponsor of Hindutva. But unfortunately, owing to the meekness shown by the congress leaders of the time, certain fanatic Muslim leaders twisted and turned things as per their whims and fancies.

A Muslim League leader Fazlul Haq in Karachi had blurted that Mohammad Bin Kasim conquered all Bharat with the aid of a few Muslim soldiers in 712 AD. He had blustered that there were eight crore Muslims at that time and could easily defeat Hindus. Certain Muslim fanatics hold such boastful notions today also but since 2014, Hindus have started asserting themselves reducing these tendencies to irrelevance. Moreover, many Muslim leaders have started joining hands with Hindu nationalist forces. This transformation could only be ascribed to the realist ideas of Sawarkar.

Savarkar was extremely progressive in his approach. Though he revered Tilak all his life, he did not hesitate while opposing the latter particularly when he stood against the reformist policies of Shahu Maharaj of Kolhapur princely state. Sawarkar and K. B. Hedgewar lent unconditional support to Shahu Maharaj. Savarkar heavily came upon the seven shackles (Saptashrunkhala) of the Hindu Religion namely, 1. Vedoktabandi (ban on access to Vedic literature to non-Brahmins including Dalits), 2.Vyavasaayabandi (ban on an individual’s choice to follow the profession of his liking), 3.Sparshabandi (untouchability), 4. Sindhubandi (ban on sea voyages), 5.Shuddhibandi (prevention of purification of religious converts), 6.Rotibandi (prohibition on inter-caste dining), 7. Betibandi (prohibition on inter-caste marriage) proposed overhauling changes in Hindu society.

Savarkar was an embodiment of strength (Kshatrabal) and scientific temperament and ideals based on reason. At a time when Bharat is poised to take up a leadership role in world politics, Savarkar’s ideas have become more relevant in determining our domestic and foreign policy matters. The inauguration of the ‘New Parliament’ building in New Delhi at the hands of PM Narendra Modi on the occasion of Savarkar’s 140th birth anniversary is a rightful tribute to this great son of Bharat.

(The author Assistant Professor of Political Science at Shyam Lal College, University of Delhi)