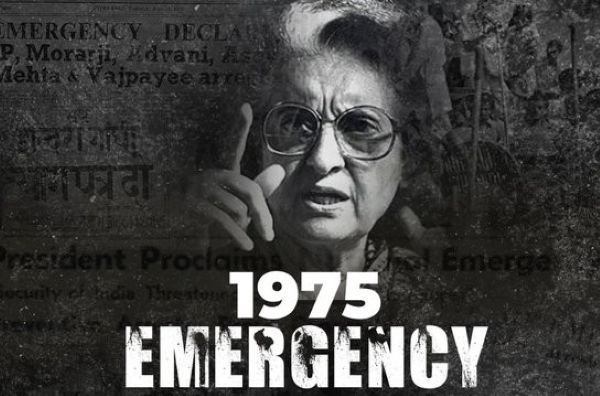

Nation observes 50th anniversary of Emergency

Law Kumar Mishra

Morning of 26 June 1975, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi addressed the nation on All India Radio, stating: “The President has proclaimed an Emergency,” and reassuring the country, “There is no need to panic.”

At that time, I was working with The Searchlight. My duty shift was the morning one—from 8 AM to 2 PM.

Believe it or not, the head of the Intelligence Bureau (IB) in Bihar, who used to regularly visit our newsroom during the JP movement to collect leftover press releases and signed statements from the Sangharsh Samiti, had no idea until that morning that the Emergency had been imposed.

He was on friendly terms with several colleagues in the editorial and reporting teams. When the chief sub-editor on duty told him, “You won’t be getting any old press releases now,” he didn’t take it well. But once he was informed that the Emergency had been declared and no leader would dare come to the press anymore, he immediately asked for details and, declining even a cup of tea, left in haste in his Willy’s jeep.

At that time, Patna lacked major hotels or guest houses. The non-Congress MLAs had resigned, and no official accommodations remained for opposition meetings. Even Bailey Road was desolate; beyond Sheikhpura, there was barely any settlement.

It was at the large cold storage owned by the late Mundar Shah—which housed Arya Niketan—that opposition leaders held their secret meetings. His son, Ganga Prasad (who later became the Governor of Sikkim), selected the onion storage warehouse as the venue.

Senior leaders like Rajendra Singh Rajju Bhaiya, Bhausaheb Deoras, Govindacharya, and Kailashpati Mishra would gather in that onion warehouse.

Outside the house, intelligence personnel kept watch. To avoid being identified, entry to the premises required coded communication—even Arya Niketan staff at the gate had designated signals. Leaders had to imitate animal or bird sounds to confirm their identity at the cold storage.

A tea vendor at Patna Junction had the job of identifying key Jan Sangh leaders. Each leader was given code names from the Ramayana. After disembarking near Rajvanshinagar, they’d stop at another tea stall, where they were re-identified using Mahabharata character names. Finally, at the cold storage gate, they would make an animal or bird call for access.

Kailashpati Mishra, later Governor of Gujarat, was known simply as “Tauji.” There was no gas cylinder in those days—food was cooked on firewood and cow dung cakes. Water came from a well, and Kamla Devi, Ganga Babu’s wife, cooked for everyone as the household staff had been dismissed. The house’s owner had already been arrested.

Many socialist leaders and student activists were admitted under the guise of medical treatment in the junior doctors’ quarters at Patna Medical College Hospital, which had been converted into a prison ward—Lalu Prasad was among them. Others were held in Bankipur and Phulwari jails.

Gautam Sagar Rana, arrested in Hazaribagh, was taken first to the Deputy Commissioner’s residence before jail, as wives of senior district officials wanted to see him.

As for press censorship, Patna didn’t witness blackouts like in Delhi. The Press Information Bureau (PIB) office was right next to The Searchlight, behind a petrol pump. Yadunath Sinha was the in-charge—well-liked by senior reporters and sub-editors, and always a gracious host after dusk.

For a time, a Joint Secretary from the Home Department was made the censor officer. He personified the saying, “A little knowledge is a dangerous thing.”

One day, our editor S.R. Rao mentioned the rising vegetable prices in an editorial—it was not approved. As a result, the next day’s editorial column appeared blank.

Later, Yadunath Sinha of PIB took over censorship duties. A former journalist himself, he understood both news and opinion.

After that, cooperation between reporters, editors, and the censor improved, with growing mutual respect. PIB/DPR press releases began getting more space in the paper.

Chief Minister Dr. Jagannath Mishra, also a former journalist, wasn’t harsh. His predecessor Abdul Ghafoor, upset by the JP movement, had accused The Searchlight of printing “false and concocted stories” and had delisted the paper, instructing:

“The Searchlight is bent upon publishing false and concocted stories. It should be delisted at once, and the order should be implemented effectively.”

Dr. Mishra, however, was more cautious on that front and continued issuing government advertisements.

Throughout the 21 months of Emergency, no journalist was arrested in Patna. Only five individuals were detained under MISA, and Karpoori Thakur remained underground, reappearing only after Emergency ended—at JP’s rally in Gandhi Maidan.

Editor S.R. Rao upheld the high standards set by his illustrious predecessors—Murli Babu, M.S.M. Sharma, K. Rama Rao, T.J.S. George, and Subhash Sarkar—never compromising. That’s why leaders like Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Rajmata Scindia, and Karpoori Thakur would often visit The Searchlight to seek his counsel on political matters.

And when Emergency was lifted and a press conference was held at CM Jagannath Mishra’s residence, Indira Gandhi reportedly remarked: “Do you think they will handle the Emergency?”

Her comment referred to the rising inflation, rural unrest, and violence during the Janata Party regime. To her, Emergency was the solution to chaos.

(The author is a senior journalist based at Patna in Bihar and has covered many states across India)